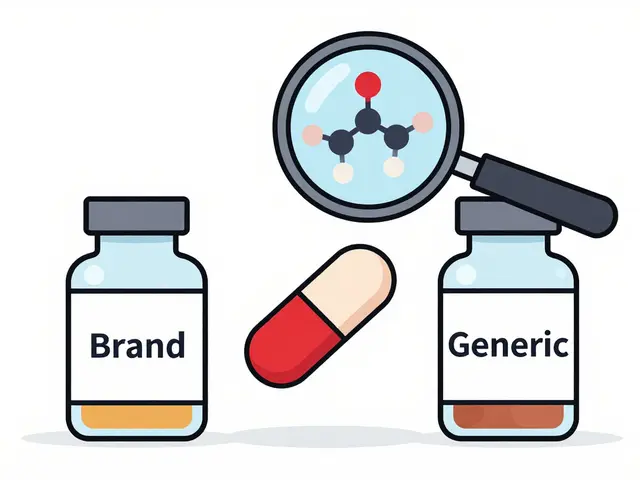

When a drug’s patent runs out, generic versions should flood the market, prices should drop by 80%, and patients should finally get affordable access. But that’s not what usually happens. Instead, big pharmaceutical companies quietly file new patents-on tiny changes like a different pill shape, a new dosage time, or a slightly altered chemical form. These aren’t breakthroughs. They’re legal tricks. And they’re called evergreening.

What Evergreening Really Is

Evergreening isn’t about inventing better medicine. It’s about stretching out a monopoly. A drug’s original patent lasts 20 years from the date it’s filed. But by the time it goes through clinical trials and gets FDA approval, that clock is already halfway gone. Companies then use a playbook of legal maneuvers to tack on extra years-sometimes decades-of exclusive sales rights.

Take AstraZeneca’s Prilosec. It was a blockbuster heartburn drug. When its patent neared expiration, they launched Nexium-a nearly identical drug with a slightly different chemical structure. Nexium wasn’t more effective. It wasn’t safer. But it had a new patent. And because it was marketed as a "new" drug, generic makers couldn’t touch it. That one switch added over a decade of high prices. Across six drugs, AstraZeneca extended patent life by more than 90 years total.

AbbVie’s Humira is another example. This autoimmune drug brings in about $40 million a day. To protect it, the company filed 247 patents. Over 100 were granted. Each one created a new legal barrier. Even when one patent expired, another was already in place. It wasn’t innovation. It was a patent thicket-designed to scare off generics with the cost and complexity of fighting dozens of lawsuits.

The Playbook: How Companies Stretch Patents

There’s a standard list of tactics used in evergreening. None require major R&D. None improve patient outcomes. But they all delay generics:

- New dosage forms: Switching from a pill to a liquid, or from once-daily to extended-release. Even if the active ingredient is unchanged.

- New combinations: Bundling two old drugs into one pill. Patent the combo, not the components.

- Orphan drug designation: Claiming a drug treats a rare disease-even if it’s widely used for common conditions-to get seven extra years of exclusivity.

- Pediatric exclusivity: Running small studies on children to earn six additional months, even if the drug isn’t meant for kids.

- Product hopping: Phasing out the old version and pushing patients to the new one. Doctors get incentives. Pharmacies get locked into contracts. Patients are forced to switch-even if their body works fine on the old pill.

- Authorized generics: The brand company launches its own generic version at a lower price. This crushes real generic competitors before they even enter the market.

- OTC switching: Moving a drug from prescription to over-the-counter. This resets the clock on exclusivity and blocks generics from entering the prescription market.

These aren’t loopholes. They’re features of the system. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to balance innovation with access. But it gave companies a roadmap to game the rules.

Why It Works: The Economics of Delay

Developing a new drug from scratch costs about $2.6 billion and takes 10 to 15 years. Evergreening? A fraction of that. A small chemistry tweak, a few months of clinical testing, and a patent lawyer’s time. The return? Billions in extra revenue.

When generics enter, prices drop 80-85% within a year. That’s the threat. Evergreening buys time. Time to keep charging $10,000 a year for a drug that costs $200 to make. For companies like AbbVie and AstraZeneca, evergreening isn’t optional-it’s core to their business model.

Harvard researchers found that 78% of new patents on prescription drugs are for existing drugs, not new ones. That’s not innovation. That’s financial engineering. And it’s working. Between 2000 and 2020, the average patent life for top-selling drugs extended from 12 years to over 18 years-mostly through evergreening.

The Human Cost

Behind every patent extension is a patient who can’t afford their medicine.

Humira treats rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and psoriasis. Millions rely on it. But with no generics, many pay $5,000 to $10,000 a year. Some skip doses. Some ration. Some go without. In the U.S., one in four patients with chronic conditions says they’ve skipped medicine because of cost.

It’s worse in low- and middle-income countries. The WHO called evergreening a direct barrier to affordable medicines. A drug that’s protected in the U.S. might be unaffordable in India or Kenya-even if the generic version is perfectly safe and effective.

And it’s not just about price. Evergreening distorts prescribing. Doctors are pushed toward the newest branded version, even if the old one works fine. Pharmacists are locked into exclusive distribution deals. Patients have no real choice.

Who’s Fighting Back?

Regulators are starting to push back.

In 2022, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission sued AbbVie over Humira’s patent strategy, calling it an illegal monopoly. The FTC argued that the 247 patents were a deliberate effort to block competition. The case is ongoing.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs starting in 2026. If the government can cap prices, the financial incentive for evergreening shrinks. Why spend millions on patent extensions if the government will force you to lower your price anyway?

Europe’s EMA now requires proof of "significant clinical benefit" before granting extra exclusivity for modified drugs. That’s a big shift. No more patents for cosmetic changes.

And in Canada, Australia, and India, courts have repeatedly thrown out patents on trivial modifications. In 2021, India’s Supreme Court rejected a patent on a cancer drug version that was just a salt form-ruling it lacked "inventive step." That decision sent shockwaves through the industry.

What’s Next?

Companies aren’t giving up. They’re just getting smarter.

Now they’re turning to biologics-complex drugs made from living cells. These are harder to copy. Even if a generic maker replicates the active ingredient, the manufacturing process is so intricate that regulators treat them as new drugs. That’s a new frontier for evergreening.

Some are using pharmacogenomics: patenting genetic tests that predict who responds to the drug. If you need a test to use the drug, and that test is patented, you can’t use the generic without paying extra.

And then there’s "supragenerics"-when the brand company launches its own generic under a different name. It looks like competition, but it’s still the same company, same factory, same profit margin. Patients think they’re getting a deal. They’re not.

These aren’t accidents. They’re calculated moves. And they’ll keep happening unless the rules change.

Can Anything Be Done?

Yes-but it takes pressure.

- Policy reform: Congress needs to close the loopholes in Hatch-Waxman. No more patents for minor changes. No more pediatric exclusivity for drugs never tested on kids.

- Transparency: All patent filings should be public. No secret patent thicketing.

- Generic incentives: Reward companies that challenge bad patents. Make it cheaper to fight.

- Public pressure: When patients speak up, lawmakers listen. Demand transparency. Ask your doctor: "Is this drug really better-or just newer?"

Evergreening isn’t inevitable. It’s a choice. And we can choose differently.

Is evergreening legal?

Yes, for now. Evergreening exploits legal gray areas in patent law and regulatory rules. While courts in some countries have struck down patents for trivial changes, in the U.S. and many other places, these tactics are still allowed as long as they technically meet patent office requirements. That doesn’t mean they’re ethical-or good for patients.

Does evergreening improve patient outcomes?

Almost never. Studies show that the vast majority of evergreened drugs offer no meaningful clinical benefit over the original. In some cases, like switching from a pill to a capsule, patients report worse side effects. The goal isn’t better health-it’s higher profits.

How long can a drug’s exclusivity last with evergreening?

Original patents last 20 years from filing, but drug approval takes 7-10 years. With evergreening, total exclusivity can stretch to 25, 30, or even 35 years. Humira’s patent strategy could extend its exclusivity until 2034-nearly 40 years after its first approval.

Are there any drugs that haven’t been evergreened?

Yes-but they’re rare. Most blockbuster drugs (those making over $1 billion a year) are targeted. Drugs for rare diseases, older generics, or those with weak patent positions are less likely to be evergreened. But for the top-selling medications-heart drugs, diabetes meds, biologics-evergreening is the norm, not the exception.

Can I tell if my drug is being evergreened?

Look at the timeline. If your drug was approved 15+ years ago and suddenly has a "new" version with a higher price, it’s likely being evergreened. Check the active ingredient-does it match the original? If yes, and the new version is marketed as superior without clinical proof, you’re probably seeing a product hop. Ask your pharmacist or doctor: "Is there a generic version of this? Why isn’t it available?"

Write a comment