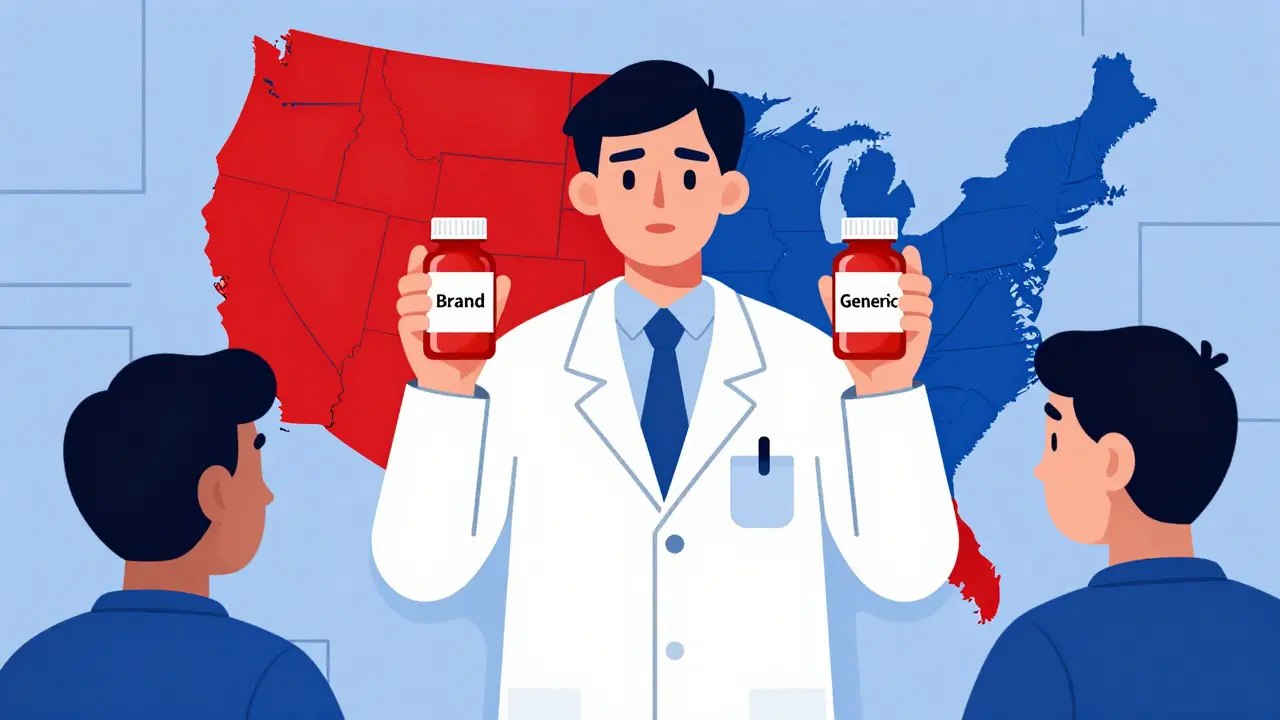

Every year, Americans fill over 6 billion prescriptions. Nearly 93% of them are for generic drugs. But here’s the catch: whether you get a generic version automatically-or even at all-depends on which state you live in. There’s no single national rule. Instead, you’ve got 50 different sets of rules, each with its own twists, exceptions, and hidden traps. Some states make pharmacists swap brand-name drugs for generics unless you say no. Others require you to give a clear yes before they can switch. And in a few places, certain life-saving drugs can’t be substituted at all-even if they’re technically identical.

Why Do State Laws on Generic Substitution Even Exist?

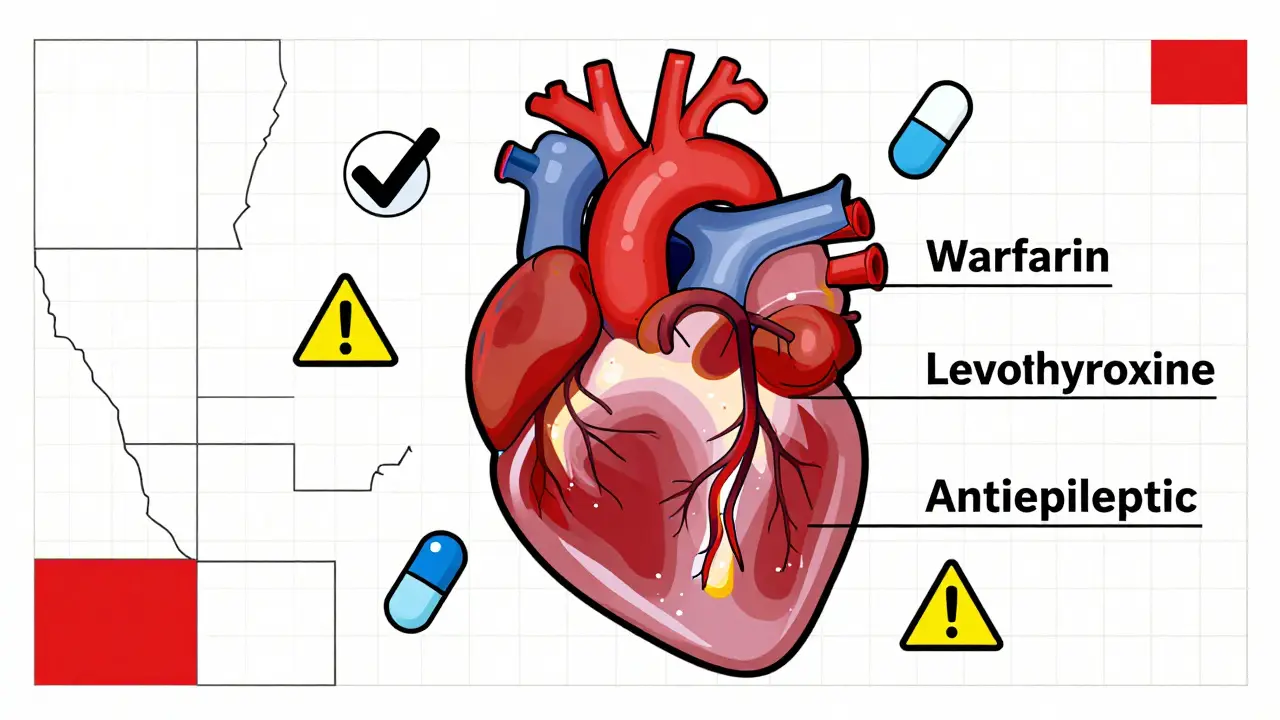

The push for generic substitution started in the 1980s after Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act. It created a fast-track approval process for generic drugs, proving they work just like brand-name versions. The goal? Save money. And it worked. Since 2009, generics have saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.7 trillion. That’s billions saved every year, mostly through state-level laws that encourage or require pharmacists to substitute. But saving money isn’t the only concern. Patient safety matters too. Some drugs have a narrow therapeutic index-meaning the difference between a dose that works and one that harms you is tiny. Warfarin, levothyroxine, and certain epilepsy drugs fall into this category. Even small changes in how your body absorbs the drug can lead to serious problems. So states had to decide: do we prioritize cost savings, or do we protect patients who might be sensitive to even minor differences?The Four Big Ways State Laws Differ

Not all state laws are created equal. They vary in four key ways:- Pharmacist Duty to Substitute - In 22 states, pharmacists must substitute a generic unless the doctor or patient says no. In the other 28 states and D.C., substitution is optional. The pharmacist can choose to give the brand-name drug even if a generic is available.

- Patient Consent - Thirty-two states use presumed consent: if you don’t say anything, the generic goes in. Eighteen states require explicit consent: you have to say, “Yes, give me the generic.” That means in New York, your pharmacist asks you every time. In Texas, they just swap it unless you object.

- Notification Requirements - Forty-one states require pharmacists to tell you after they’ve made a switch. That could be a printed notice, a phone call, or a note on your receipt. But in nine states, you might never know you got a different pill unless you check the label yourself.

- Liability Protection - Thirty-seven states shield pharmacists from lawsuits if they follow the rules. If you have a bad reaction after a legal substitution, the pharmacist usually can’t be held responsible. But in states without this protection, pharmacists are more cautious-and might avoid substitution altogether.

Where It Gets Complicated: Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

The biggest controversy isn’t about aspirin or statins. It’s about drugs like warfarin (a blood thinner), levothyroxine (for thyroid issues), and antiepileptic medications. These aren’t just any pills. A 5% change in blood levels can mean the difference between control and crisis. Fifteen states have extra rules for these drugs. Kentucky, for example, bans substitution for digitalis and seizure meds. Minnesota had documented cases where patients on warfarin had dangerous bleeding episodes after switching generics-even though the FDA rated them as equivalent. The FDA says all Orange Book-listed generics are safe. But real-world experience tells a different story. Some patients just respond differently to different formulations. That’s why many doctors write “Dispense as Written” (DAW) on prescriptions. A 2023 survey by the Life Raft Group found that 28% of patients with rare diseases were told by their doctors to refuse substitution. For them, stability matters more than savings.

Biosimilars: The New Frontier

Biosimilars-generic versions of complex biologic drugs like Humira or Enbrel-are the next wave. As of 2023, 49 states and D.C. have laws covering them. But they’re even trickier than regular generics. Unlike pills, biologics are made from living cells. No two batches are exactly alike. The FDA now designates some as “interchangeable,” meaning they can be swapped without a doctor’s approval. Florida requires pharmacies to create a formulary to ensure biosimilar substitutions won’t harm patients. Iowa says to stick with the FDA’s Orange Book. Hawaii is the strictest: you need consent from both the doctor and the patient for any substitution of antiepileptic biosimilars. That’s not just caution-it’s a legal hurdle.What This Means for Patients

If you live near a state border, you’ve probably run into this: you get your prescription filled in one state, then go to a pharmacy in the next. Suddenly, your pill looks different. Or worse-you’re told you can’t get the generic you’ve been using for years. A pharmacist in New York told Reddit users: “I have patients who live in New Jersey. They come in confused because I ask if they want the generic, but their pharmacy across the line just swaps it. They think I’m being difficult.” Patients with chronic conditions are especially affected. A 2022 survey found that 41% of cancer patients worried about substitution for critical drugs. One woman in Ohio described switching from her brand-name insulin to a generic-only to have her blood sugar spike. She had to switch back. Her doctor never told her substitution was even possible.What This Means for Pharmacists

Pharmacists are on the front lines. They’re expected to know the laws of 50 states, track which drugs are on state-specific NTI lists, and remember whether their state requires written consent, verbal consent, or just a note on the bottle. On average, pharmacists spend 12.7 minutes per prescription verifying substitution rules. That’s time they could spend counseling patients. Chain pharmacies use software that auto-checks state laws-83% now have it. But independent pharmacies? Many still rely on printed guides and phone calls to state boards. Licensing exams now require 45 to 60 hours of training on substitution laws. Still, mistakes happen. A 2023 study found that 18.3% of prescriptions filled in chain pharmacies cross state lines. One wrong substitution could mean a lawsuit, a complaint, or worse-a patient’s health crisis.

Write a comment