Most people think of vitamin D as just a bone vitamin. You take it to avoid rickets or to keep your skeleton strong. But that’s only the tip of the iceberg. Vitamin D acts like a hormone - not just a nutrient - and it talks directly to your endocrine system. It influences your thyroid, your pancreas, your adrenal glands, and even your immune cells. If your vitamin D levels are off, it doesn’t just affect your bones. It can throw off your blood sugar, your blood pressure, your immune response, and your hormone balance. The real question isn’t whether you need it - it’s how much you need, and why some people never feel better even after taking it.

How Vitamin D Actually Works in Your Body

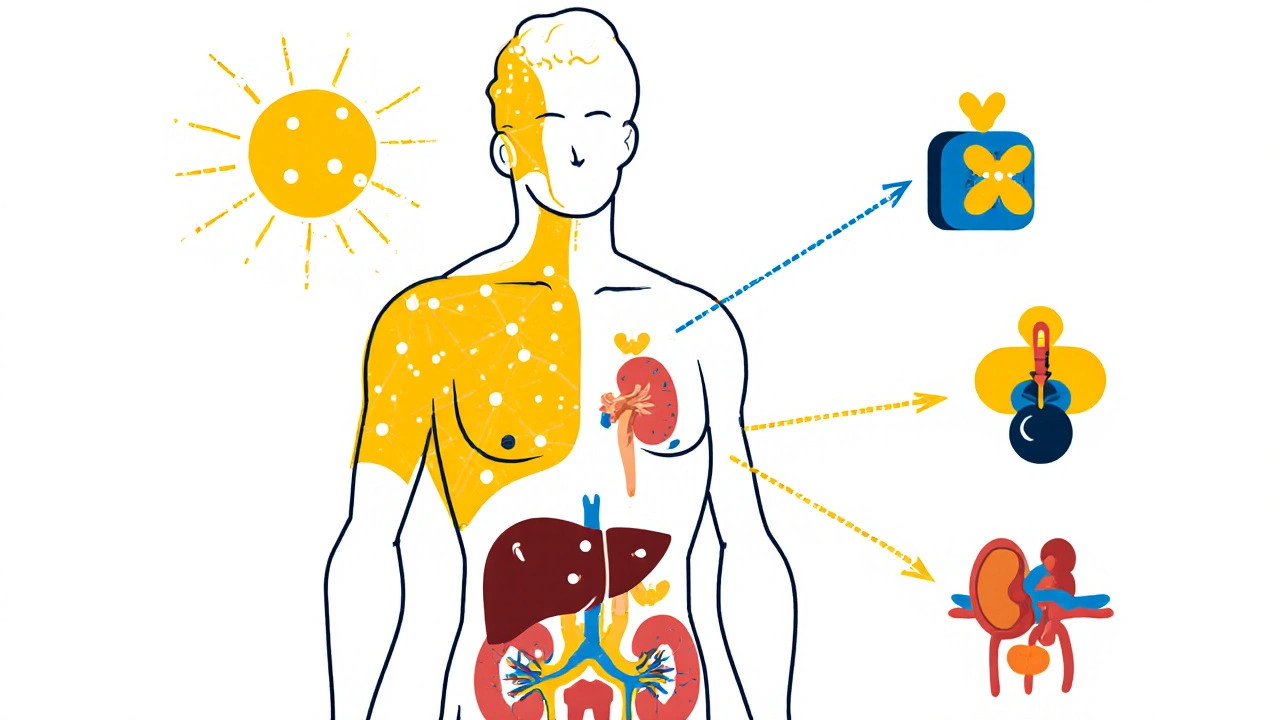

Vitamin D isn’t active when you get it from the sun, food, or a pill. It has to be transformed twice before your body can use it. First, your liver turns it into 25-hydroxyvitamin D - that’s the version doctors test for. Then, your kidneys convert it into 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, the active hormone form. This final version binds to receptors in almost every cell in your body. That’s not a small thing. It means vitamin D isn’t just helping your gut absorb calcium. It’s turning genes on and off in your pancreas, your blood vessels, your brain, and your fat cells.

The classic job of vitamin D is keeping calcium levels steady. Your body needs calcium for your heart to beat, your muscles to contract, and your nerves to fire. If your blood calcium drops too low, your parathyroid glands kick in. They release parathyroid hormone (PTH), which pulls calcium from your bones and tells your kidneys to hold onto it. But here’s the catch: if you don’t have enough vitamin D, your body can’t absorb calcium from your food - no matter how much you eat. That forces your parathyroid glands to work overtime, leading to secondary hyperparathyroidism. Over time, this eats away at your bone density and increases fracture risk. Studies like the Framingham Heart Study showed people with vitamin D levels below 15 ng/mL had a 31% higher chance of breaking a bone.

The Two Faces of Vitamin D: Endocrine vs. Autocrine

There are two ways vitamin D works in your body. The first is the endocrine system - the slow, controlled, blood-borne version. Your kidneys make the active hormone based on calcium levels, PTH, and phosphate. This system is like a thermostat: it keeps your blood calcium locked between 8.5 and 10.5 mg/dL. That’s non-negotiable for survival.

The second way is autocrine or paracrine - local, on-the-spot production. Many tissues, like immune cells, the pancreas, and even your skin, can make their own active vitamin D right where they need it. This doesn’t affect your blood calcium. It’s like a private message between cells. For example, when a macrophage (an immune cell) detects an infection, it turns on the enzyme that makes active vitamin D locally. That helps it fight off bacteria. But here’s the problem: your blood test for 25(OH)D doesn’t tell you what’s happening inside those cells. Someone with a normal blood level might still be running on empty in their immune system. That’s why some people feel awful despite having "normal" vitamin D.

What’s a "Normal" Level Anyway?

This is where things get messy. The Endocrine Society says you need at least 30 ng/mL to be sufficient. The Institute of Medicine says 20 ng/mL is enough for 97.5% of people. Which one’s right? It depends on what you’re trying to protect.

If you only care about preventing rickets or osteoporosis, 20 ng/mL might be fine. But if you’re trying to keep your immune system sharp, your insulin sensitivity high, or your blood pressure in check, you might need more. Data from NHANES shows people with levels under 20 ng/mL have a 25% higher risk of high blood pressure. Studies also link low vitamin D to higher rates of type 2 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and even depression - though causation is still debated.

The problem? Blood tests don’t tell the whole story. About 85% of vitamin D in your blood is stuck to a protein called vitamin D binding protein (DBP). Only the free 0.03% is available to your cells. Some people have genetic variations in DBP that make more or less vitamin D available - even if their total blood level looks fine. That’s why two people with the same test result can feel totally different.

Who Needs Supplementation - and How Much?

Not everyone needs a supplement. But some groups are at high risk:

- People with limited sun exposure (indoor workers, northern latitudes in winter)

- Older adults (skin makes less vitamin D with age)

- People with darker skin (melanin blocks UVB rays)

- Obese individuals (vitamin D gets trapped in fat tissue)

- Those with malabsorption issues (celiac disease, Crohn’s, gastric bypass)

The Endocrine Society recommends 600-2,000 IU per day for adults under 70, and 800-2,000 IU for those over 70. But if you’re obese, you might need 2-3 times that. One study found obese people needed 3,000 IU daily just to hit 30 ng/mL - while normal-weight people only needed 1,500 IU. For someone with celiac disease, a short course of 50,000 IU weekly for 8 weeks might be needed before switching to daily maintenance.

Don’t go overboard. Toxicity is rare, but it happens. Levels above 150 ng/mL can cause hypercalcemia - too much calcium in your blood. That can lead to kidney stones, nausea, confusion, and even heart rhythm problems. Most people won’t hit that level unless they’re taking 10,000 IU or more daily for months. But if you’re already taking calcium supplements or have kidney disease, you’re at higher risk.

Why Some People Don’t Feel Better - Even With High Doses

You’ve probably heard stories. Someone takes 10,000 IU a day for six months, their blood level jumps from 18 to 65 ng/mL - and they still feel tired, achy, and depressed. Meanwhile, another person takes 2,000 IU and feels like a new person in two weeks.

There are a few reasons for this.

First, symptoms like fatigue and muscle weakness can come from many places - low iron, thyroid problems, sleep apnea, depression. Vitamin D deficiency might be one piece, not the whole puzzle.

Second, your body takes time to respond. It can take 2-3 months for your 25(OH)D level to stabilize after you start supplementing. Testing too soon gives you a false picture.

Third, genetics matter. Some people have a variation in the CYP2R1 gene that makes their liver worse at converting vitamin D into its first form. Others have DBP variants that bind vitamin D too tightly. These people need higher doses just to reach the same blood level as someone without those genes.

Finally, the autocrine system might still be starved. Even with high blood levels, your immune cells or pancreatic beta cells might not be making enough active vitamin D locally. That’s why future research is focusing on measuring tissue-specific activity - not just blood levels.

The Big Controversy: Does It Prevent Disease?

There’s a huge gap between what lab studies show and what big clinical trials find.

In test tubes and mice, vitamin D reduces inflammation, boosts insulin production, and slows tumor growth. But when you test it in tens of thousands of people over years - like in the VITAL trial - the results are underwhelming. Taking 2,000 IU daily for over five years didn’t lower cancer or heart disease rates. That’s why big medical groups like the US Preventive Services Task Force say there’s not enough evidence to recommend routine screening or supplementation for healthy adults.

But here’s the twist: those trials were designed to test prevention in the general population. They didn’t target people who were already deficient. When you look at studies that focus on people with levels under 20 ng/mL, the benefits are clearer - especially for bone health. The real question isn’t whether vitamin D works. It’s whether we’re giving it to the right people, at the right dose, for the right reason.

What Doctors Are Actually Doing

Most endocrinologists don’t test vitamin D in healthy people. They reserve testing for high-risk groups: people with osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, malabsorption, or unexplained bone pain. In these groups, deficiency is common - up to 80% in some cases.

But patient demand is high. A 2022 survey found 68% of physicians say they order unnecessary vitamin D tests because patients ask for them. Social media and supplement marketing have fueled the idea that vitamin D is a miracle cure. That’s not accurate. It’s a critical hormone - but it’s not a magic bullet.

What works best? A targeted approach. If you’re at risk, get tested. If you’re deficient, supplement with 1,000-2,000 IU daily. Recheck in 3 months. If you’re not at risk and feel fine, you probably don’t need a test or a pill. Sunlight (10-20 minutes on arms and face, 2-3 times a week) and food (fatty fish, egg yolks, fortified milk) are enough for most.

What’s Next for Vitamin D Research

Scientists are moving beyond blood tests. The NIH is funding a project called the Vitamin D Exposome Project to measure how vitamin D affects gene activity in individual cells. They’re using RNA sequencing to see which genes turn on in immune cells when vitamin D is present - even if blood levels look normal.

Pharmaceutical companies are developing synthetic vitamin D analogs that target specific tissues. One drug, eldecalcitol, already exists in Japan and reduces fractures better than regular vitamin D by acting mainly on bone. Another, VDRM-110, is being tested to help insulin production in type 2 diabetes without raising calcium levels.

The future isn’t about taking more vitamin D. It’s about knowing who needs it, how much, and why - based on genetics, lifestyle, and tissue-level activity, not just a number on a lab report.

Bottom Line: Don’t Guess. Test If You’re at Risk.

Vitamin D is essential. But it’s not a cure-all. If you’re not getting sun, are over 65, have dark skin, are obese, or have digestive issues - get your 25(OH)D level checked. If it’s under 30 ng/mL, supplement with 1,000-2,000 IU daily. Wait 3 months, then retest. Don’t take 10,000 IU just because you read it online. And don’t expect it to fix everything. It’s one piece of your endocrine puzzle - not the whole picture.

Write a comment