TRIPS Changed How the World Gets Medicine

Before 1995, if you lived in India, Brazil, or Thailand, you could buy life-saving HIV drugs for a few dollars a month. Generic manufacturers made them without permission from big drug companies because those countries didn’t allow patents on medicines. Then came the TRIPS agreement is a World Trade Organization treaty that sets minimum global standards for intellectual property, including 20-year patents on pharmaceuticals. Also known as Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, it was signed in 1994 and took effect on January 1, 1995. Overnight, countries had to change their laws. Patents became mandatory. Prices for HIV drugs jumped from $100 a year to over $10,000. Millions couldn’t afford treatment. This wasn’t an accident. It was the design.

What TRIPS Actually Requires

TRIPS isn’t vague. It’s precise-and harsh for public health. Article 33 says every country must give pharmaceutical patents for at least 20 years from the filing date. That means even if a drug was invented in the U.S. in 2005, no generic version can legally be made until 2025, even if it’s sold in a country where people earn $2 a day. Article 27 says you can’t patent a naturally occurring substance, but you can patent a slightly modified version of it-something drug companies do constantly to extend their monopoly.

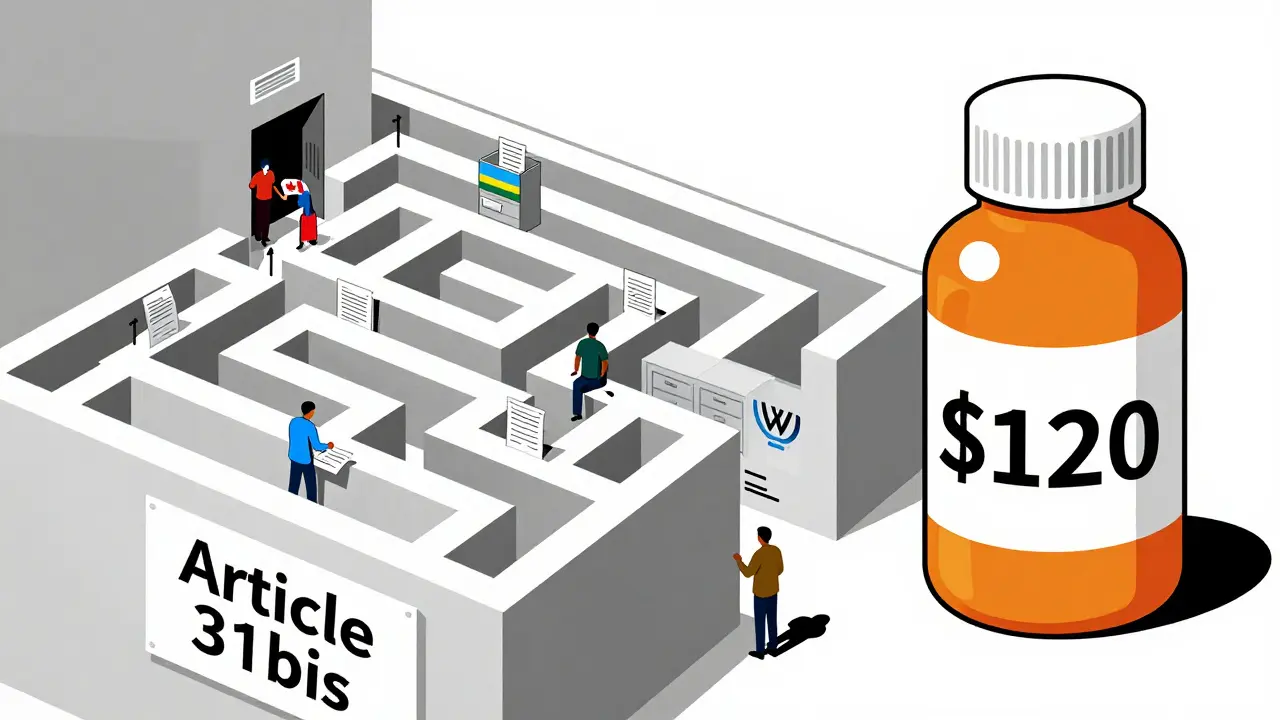

Article 31 lets countries issue compulsory licenses to make generic versions without the patent holder’s consent, but only under strict conditions. The license must be mostly for the domestic market. So if you’re a small country like Rwanda with no drug factories, you can’t legally import generics made in India. That’s where the 2005 amendment came in-Article 31bis. It was supposed to fix this. But it didn’t.

The One Time It Actually Worked (And Why It’s Broken)

In 2007, Rwanda needed 200,000 doses of an HIV drug. It had no factories. India could make it cheaply. So Rwanda asked Canada to produce it under a compulsory license and export it. The process took four years. Why? Because every step required paperwork approved by three governments, three legal teams, and the WTO. Canada had to notify the WTO 15 days before shipping. Rwanda had to prove it couldn’t make the drug itself. The patent holder had to be paid. The shipment had to be labeled to avoid diversion. The whole thing cost $1.3 million. The same medicine, made locally in India, would’ve cost $120,000.

Médecins Sans Frontières called it “unworkable.” So did Apotex, the Canadian company that made the pills. No country has used the system since. Not because no one needs it. Because it’s too slow, too complex, and too risky. A 2019 Duke University study found 92% of low-income countries have less than two staff members handling all patent and medicine policy. Most don’t even know where to start.

Why Countries Don’t Use the Loopholes

Thailand used compulsory licenses in 2006 for HIV, heart, and cancer drugs. Prices dropped by 30% to 80%. Then the U.S. punished them. They lost $57 million a year in export benefits. Brazil did the same in 2007 with efavirenz. The U.S. put them on a “Priority Watch List.” South Africa tried in 1997. Thirty-nine drug companies sued them. The case was dropped only after global protests.

It’s not just about money. It’s about fear. A 2017 study of 105 countries found 83% had never issued a compulsory license-not because they didn’t need to, but because they were scared of trade retaliation, diplomatic pressure, or being labeled “uncooperative.” The UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines documented 423 threats of trade sanctions between 2007 and 2015. That’s not policy. That’s coercion.

Voluntary Licenses Aren’t the Answer

Big pharma says, “We’re not the problem. We give voluntary licenses.” The Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) is often cited as proof. Since 2010, MPP has licensed 44 patented medicines for use in low-income countries. Sounds good? Look closer. Those 44 cover less than 1.2% of all patented drugs. Most are for HIV. Very few are for cancer, diabetes, or mental health. And 73% of those licenses are only valid in sub-Saharan Africa-even though the diseases exist everywhere.

Voluntary licenses are not rights. They’re favors. And they can be pulled. In 2020, Gilead Sciences, maker of the hepatitis C drug sofosbuvir, granted licenses to 112 countries-but not to Brazil, Russia, or South Africa. Why? Because they’re middle-income. The system isn’t designed for equity. It’s designed for profit.

TRIPS-Plus Is Making Things Worse

TRIPS is bad enough. But now, rich countries are slipping even harsher rules into trade deals. The U.S.-Jordan Free Trade Agreement, signed in 2011, extended patent terms beyond 20 years. It blocked generic approval even after the patent expired. Similar clauses exist in deals with Colombia, Morocco, and Australia. The WTO says 86% of its members have added these “TRIPS-plus” rules. On average, they add 4.7 extra years of monopoly.

That’s not just legal. It’s financial. Health Action International estimates TRIPS-plus provisions cost low- and middle-income countries $2.3 billion a year in lost savings from generic competition. That’s enough to cover treatment for 12 million people with HIV for a year.

What’s Changing Now?

The pandemic forced the world to look at TRIPS again. In October 2020, India and South Africa proposed a full waiver of TRIPS protections for COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments. After two years of lobbying, the WTO agreed in June 2022 to a limited waiver-for vaccines only. No diagnostics. No therapeutics. No manufacturing tech. And even that waiver has a sunset clause: it expires in 2025.

But the pressure hasn’t stopped. In September 2024, the UN held its first-ever High-Level Meeting on Pandemic Prevention. The final declaration called for “reform of the TRIPS Agreement to ensure timely access to health technologies during health emergencies.” That’s the first time the UN has directly called for TRIPS changes. WHO’s 2023 Digital Health Strategy now includes TRIPS flexibilities as a key tool for enabling local production of digital medical tools. That’s new. It means the debate is expanding beyond pills to AI diagnostics, telehealth platforms, and vaccine delivery systems.

The Real Cost of Patent Monopolies

There are 2 billion people in the world who don’t have regular access to essential medicines. The WHO says 80% of that gap is because of patent barriers. In the U.S., 89% of prescriptions are generics. In low-income countries, it’s 28%. The same pill can cost $100 in the U.S. and $1,000 in Nigeria-not because it’s harder to make, but because the patent holder controls the supply.

The global pharmaceutical market hit $1.42 trillion in 2022. Patented drugs made up 68% of that revenue. But they’re only 12% of all prescriptions. That’s the math: 12% of drugs earn 68% of the money. The rest are cheap, effective, and generic. But they’re blocked by law.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

Big pharma wins. They get longer monopolies, higher prices, and more profits. Shareholders win. The CEOs of Pfizer, Moderna, and Roche earned over $20 million each in 2022. Countries like Canada and Switzerland win-they’re home to patent-heavy companies and get paid royalties.

Who loses? The 1.2 million people who died of HIV in 2023 because they couldn’t afford treatment. The 200,000 children who died of pneumonia because antibiotics were too expensive. The 7 million people with diabetes who skip insulin doses because they can’t pay. The people in rural India who walk 50 kilometers for a pill that should cost $1.

What Needs to Change

There are three fixes that would work immediately:

- Expand the 31bis system so countries can import generics without jumping through 78 bureaucratic hoops.

- Remove TRIPS-plus clauses from all trade deals. No country should be forced to give up public health rights to get a trade deal.

- Make compulsory licensing automatic during health emergencies. No need for permission. No need for negotiation. If a disease kills people, generics can be made.

It’s not about being anti-patent. It’s about being pro-life. The law was written to protect innovation. But innovation doesn’t mean profit. It means saving lives. Right now, TRIPS protects the first and ignores the second.

What You Can Do

If you live in a rich country, ask your government: Why are we blocking access to medicine in other countries? Why are we supporting trade deals that make people pay more for insulin? Why are we letting a treaty from 1995 decide who lives and who dies in 2025?

If you live in a low-income country, know this: you have rights under TRIPS. You just need to know how to use them. Groups like Médecins Sans Frontières and the Treatment Action Campaign have free legal toolkits. You don’t need a lawyer. You need a voice.

What is the TRIPS agreement and why does it matter for medicine?

The TRIPS agreement is a World Trade Organization treaty that requires all member countries to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceuticals. Before TRIPS, countries like India made cheap generic versions of HIV and cancer drugs. After TRIPS, those generics became illegal in most places. This forced prices up by hundreds of percent, making life-saving medicines unaffordable for millions in low-income countries.

Can countries still make generic medicines under TRIPS?

Yes, but only under strict conditions. Countries can issue compulsory licenses to produce generics without the patent holder’s permission, but only for domestic use. To import generics from another country, they must use the complex Article 31bis system, which has only been used once-in 2008 by Rwanda-and took four years to complete.

Why haven’t more countries used compulsory licensing?

Because of fear. Countries like Thailand and Brazil used compulsory licenses and faced trade sanctions, diplomatic pressure, or lawsuits from drug companies. A 2017 study found 83% of low-income countries never issued a license-not because they didn’t need to, but because they were scared of retaliation.

What’s the difference between TRIPS and TRIPS-plus?

TRIPS sets the global minimum for patent protection. TRIPS-plus refers to stricter rules added by rich countries in bilateral trade deals-like extending patent terms beyond 20 years or blocking generic approval even after patents expire. These rules are not required by WTO law but are forced on poorer countries to get trade access.

Did the COVID-19 vaccine waiver fix the TRIPS problem?

No. The 2022 WTO waiver only applied to vaccines, not to treatments, diagnostics, or manufacturing technology. It also expires in 2025. It didn’t change the rules for future pandemics. And it didn’t help countries without vaccine factories. The real solution-removing patent barriers for all health technologies-is still on the table.

Are generic medicines safe?

Yes. Generic drugs contain the same active ingredients as brand-name drugs and must meet the same quality standards set by the WHO and national regulators. In fact, 89% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are generics. The only difference is price-often 90% lower.

What’s the future of TRIPS and medicine access?

The pressure is growing. The UN, WHO, and civil society are calling for TRIPS reform. The next big fight is over diagnostic tools, cancer drugs, and digital health technologies. Without change, the UN predicts 3.2 billion people will lack access to essential medicines by 2030. The law is not set in stone. It was written by people. It can be changed by people.

Write a comment