Vancomycin Infusion Rate Calculator

Infusion Calculator

Calculate the minimum safe infusion time for vancomycin to prevent infusion reactions.

How It Works

The maximum safe infusion rate for vancomycin is 10 mg/min.

Faster infusion increases risk of flushing syndrome.

For a 1000 mg dose at 10 mg/min, minimum infusion time = 100 minutes.

For a 500 mg dose at 10 mg/min, minimum infusion time = 50 minutes.

Recommended Infusion Time

Vancomycin is a powerful antibiotic used to treat serious bacterial infections like MRSA and severe Clostridioides difficile. But for all its lifesaving power, it comes with a well-known, avoidable side effect that still catches many clinicians off guard: the vancomycin infusion reaction. Once called ‘red man syndrome,’ this reaction isn’t an allergy-it’s a predictable, rate-dependent response that happens when the drug is given too fast. And understanding how to prevent it can mean the difference between a smooth treatment and a medical emergency.

What Really Happens During a Vancomycin Infusion Reaction?

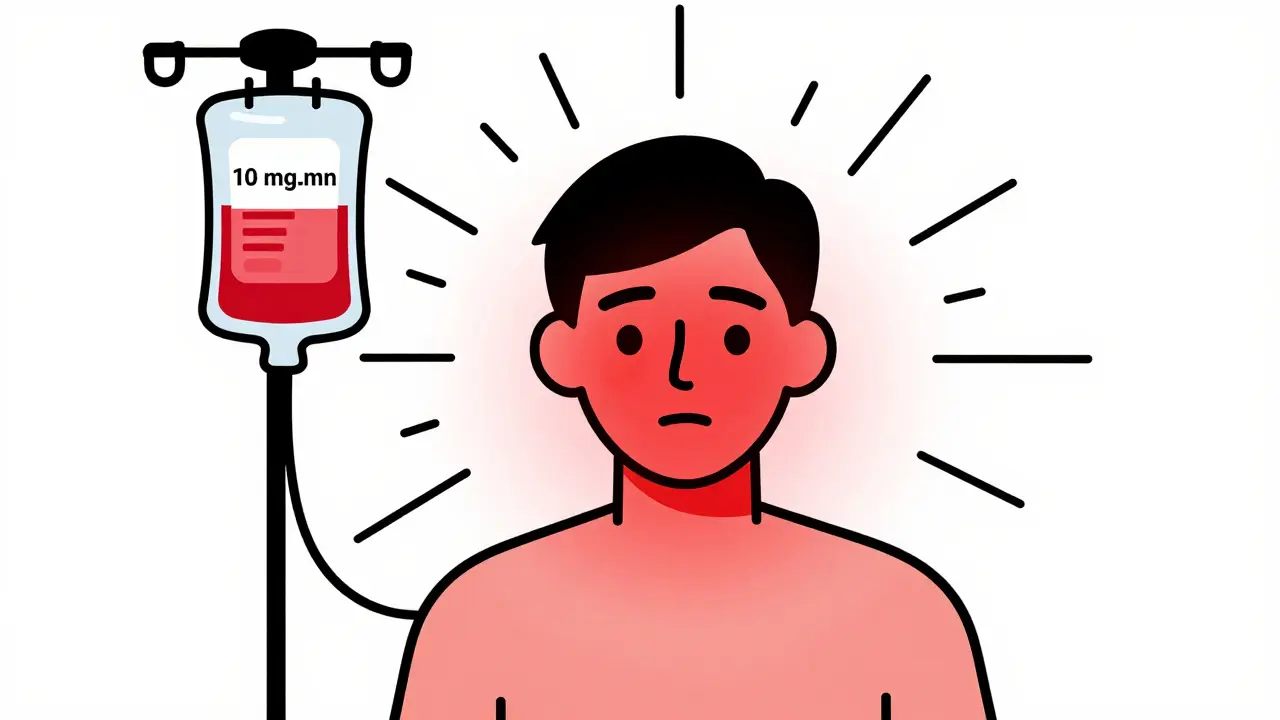

When vancomycin is infused too quickly-faster than 10 mg per minute-it triggers a direct release of histamine from mast cells and basophils. This isn’t an IgE-mediated allergic reaction like peanut or bee sting allergies. It’s an anaphylactoid reaction: same symptoms, different cause. No prior exposure needed. It can happen the very first time someone gets vancomycin.

The classic signs show up 15 to 45 minutes after starting the infusion: flushing of the face, neck, and upper chest. The skin turns red or pink, often with a warm, burning feeling. Itching follows, sometimes intensely. In more severe cases, patients may feel chest tightness, back pain, muscle spasms, or even a drop in blood pressure and a racing heart. These symptoms usually fade within 30 minutes after stopping the infusion.

Here’s the key detail: the faster you give vancomycin, the worse it gets. A 1988 study in The Journal of Infectious Diseases found that 9 out of 11 healthy adults developed the reaction when given 1000 mg over one hour. None had symptoms when given 500 mg over the same time. That’s not random-it’s dose and rate dependent. Plasma histamine levels spiked directly with the infusion speed, and the severity matched the histamine surge.

Why ‘Red Man Syndrome’ Is Outdated-and Harmful

The term ‘red man syndrome’ has been used for decades. But in recent years, the medical community has moved away from it-not just because it’s inaccurate, but because it’s offensive. The name implies a racial stereotype, reducing a physiological reaction to a caricature. In 2021, a study in Hospital Pediatrics analyzed over 21,000 allergy records and found that 61.6% of vancomycin ‘allergy’ entries still used the term ‘red man syndrome.’ After a hospital-wide education campaign replaced the term with ‘vancomycin flushing syndrome’ or ‘vancomycin infusion reaction,’ the use of the outdated term dropped by 17% in just three months.

Major institutions like UCSF, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the National Library of Medicine now use ‘vancomycin infusion reaction’ as the standard term. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology supports this shift as part of a broader effort to remove racially insensitive language from medical documentation. Terms matter. They shape how clinicians think, document, and treat patients. Using outdated, biased language can lead to misdiagnosis, unnecessary avoidance of life-saving drugs, and even harm to patient trust.

Differentiating Vancomycin Reaction from True Allergy

One of the biggest mistakes in clinical practice is labeling vancomycin infusion reactions as ‘allergies.’ That’s dangerous. If a patient is flagged as ‘allergic to vancomycin’ because they had flushing during an infusion, they might be denied the drug entirely-even when it’s the best or only option.

True vancomycin allergies are extremely rare. According to UCSF’s 2022 guideline, only 3% of patients labeled as vancomycin-allergic actually had a true IgE-mediated anaphylactic reaction. The majority-over 90%-had infusion reactions. Other serious but rare reactions like DRESS, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, or toxic epidermal necrolysis account for another 4%. That leaves less than 1% with true allergy.

Here’s how to tell them apart:

- Vancomycin infusion reaction: Flushing and itching confined to upper body, no swelling of throat or tongue, no wheezing or breathing trouble, no drop in oxygen. Happens during or right after infusion. Can occur on first exposure.

- True anaphylaxis: Swelling of lips, tongue, or airway; wheezing; low blood pressure; nausea/vomiting; loss of consciousness. Requires prior sensitization. Usually starts within minutes of starting the infusion.

Patients with true anaphylaxis need to avoid vancomycin entirely. Those with infusion reactions just need slower infusions.

How to Prevent Vancomycin Infusion Reactions

The good news? Vancomycin infusion reactions are almost 100% preventable. You don’t need fancy equipment or expensive drugs. Just time and discipline.

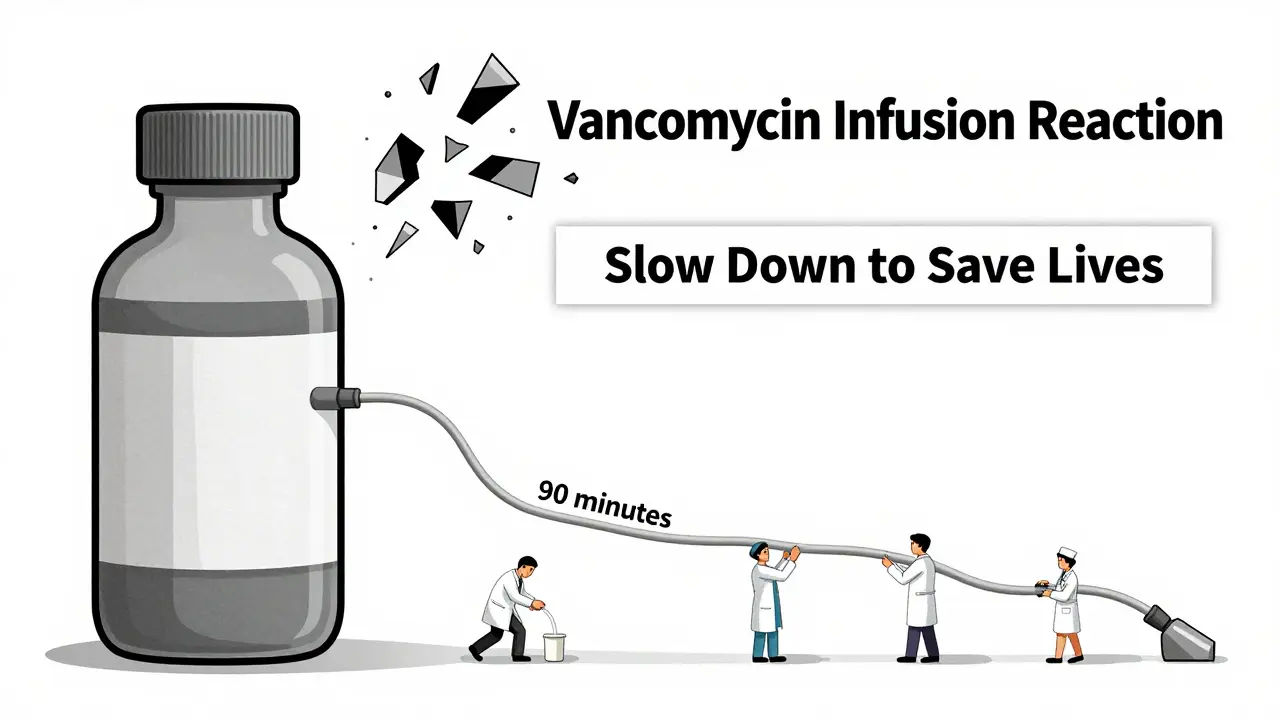

The standard recommendation from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and UCSF is simple: infuse vancomycin at a rate of 10 mg per minute or slower. That means a 1-gram dose should take at least 100 minutes to give. Many hospitals now use infusion pumps programmed to deliver vancomycin over 90-120 minutes to ensure safety.

Here’s what else helps:

- Never give vancomycin as a rapid IV push. Even a 10-minute push can trigger a reaction.

- Avoid giving vancomycin at the same time as other histamine-releasing drugs like opioids, muscle relaxants, or radiocontrast media. These can make the reaction worse.

- Don’t premedicate patients who’ve never had a reaction before. A 2018 study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine found no benefit to giving diphenhydramine or ranitidine prophylactically to first-time users. It adds cost, risk, and confusion.

- If a patient has had a reaction before and needs a faster infusion (e.g., in sepsis), consider premedication with diphenhydramine 25-50 mg IV and ranitidine 50 mg IV. But still, keep the infusion rate ≤10 mg/min.

Some clinicians think that giving vancomycin slowly will delay treatment. But studies show that even in critically ill patients, giving vancomycin over 90 minutes doesn’t impact outcomes. Speed doesn’t equal effectiveness.

What to Do If a Reaction Happens

Even with the best precautions, reactions can still occur. Here’s what to do:

- Stop the infusion immediately.

- Assess the patient: Are they breathing? Is their blood pressure stable? Is there swelling or wheezing?

- If symptoms are mild (flushing and itching only), monitor closely. Most reactions resolve on their own within 30 minutes.

- If symptoms are moderate to severe (hypotension, chest pain, difficulty breathing), treat like anaphylaxis: give oxygen, IV fluids, and consider epinephrine if there’s true anaphylaxis or severe hypotension.

- Document the event accurately: ‘Vancomycin infusion reaction,’ not ‘vancomycin allergy.’

- Adjust future doses: slow the rate, consider premedication if needed, and avoid concurrent mast cell activators.

Importantly, don’t assume the patient is ‘allergic’ after one reaction. Most will tolerate vancomycin just fine if given slowly. Dismissing vancomycin as ‘allergic’ based on a reaction you could have prevented is a missed opportunity-and potentially dangerous.

Other Drugs That Cause Similar Reactions

Vancomycin isn’t the only drug that causes histamine release. Others include:

- Amphotericin B: Causes flushing and hypotension through complement activation, not histamine.

- Rifampin: Triggers hypersensitivity via reactive metabolites binding to proteins.

- Ciprofloxacin: Rarely, can cause flushing and pruritus.

These reactions are also rate-dependent and preventable with slower infusions. Recognizing the pattern helps you manage them all.

Bottom Line: Slow Down to Save Lives

Vancomycin is a critical tool in fighting resistant infections. But its biggest risk isn’t toxicity-it’s how we give it. Infusing it too fast isn’t just a nuisance; it’s a preventable safety hazard that leads to unnecessary alarms, misdiagnoses, and sometimes, delays in care.

The solution is simple: slow the infusion. Use infusion pumps. Educate nurses and pharmacists. Update electronic records to use accurate terminology. And never label a patient ‘allergic’ to vancomycin unless they’ve had a true IgE-mediated reaction.

Every time you give vancomycin slowly, you’re not just preventing flushing. You’re keeping the drug available for the next patient who needs it. And you’re helping build a more accurate, respectful, and safer medical system.

Write a comment