Clarithromycin Alcohol Risk Calculator

This calculator assesses your risk level when combining clarithromycin and alcohol based on your consumption patterns and medical factors. Based on clinical guidelines and pharmacokinetic data, it helps you make informed decisions about alcohol use during antibiotic treatment.

Risk Assessment Results

Mixing clarithromycin and alcohol might sound harmless, but the combination can turn a simple infection treatment into a headache‑filled ordeal. Below we unpack what happens in the body, why certain side effects flare up, and how you can stay safe without missing a dose.

What Clarithromycin Actually Does

Clarithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic that fights bacterial infections by blocking protein synthesis in the microbes. First approved in the early 1990s, it’s become a go‑to for respiratory infections, skin infections, and Helicobacter pylori eradication protocols.

The drug is absorbed well when taken orally, reaches peak blood levels in about two hours, and is mainly cleared by the liver. Its long half‑life (about 3‑7 hours) means it stays in the system for a full day after the last dose.

How Alcohol Enters the Picture

Alcohol refers to ethanol, the psychoactive ingredient in drinks such as beer, wine, and spirits. The liver metabolises alcohol using enzymes like alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and, indirectly, the cytochrome P450 system.

When you sip a cocktail while on clarithromycin, both substances compete for the liver’s processing power. This competition can amplify side effects, alter drug levels, and, in rare cases, lead to serious complications.

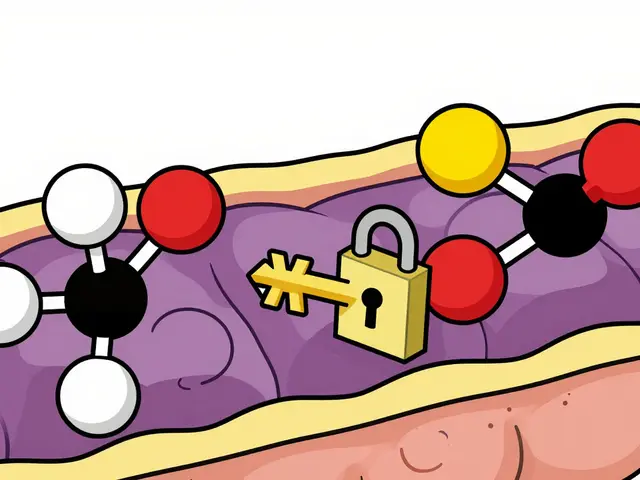

The Key Enzyme: CYP3A4

Clarithromycin is a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4, one of the liver’s main cytochrome P450 enzymes. CYP3A4 handles the breakdown of many drugs, including some statins, calcium‑channel blockers, and even certain anti‑anxiety meds.

When you drink alcohol, the liver’s ADH pathway gets busy, and the overall metabolic load spikes. Because clarithromycin already “clogs” CYP3A4, the extra burden from alcohol can push liver enzymes into overdrive, resulting in higher blood concentrations of clarithromycin and an increased chance of toxicity.

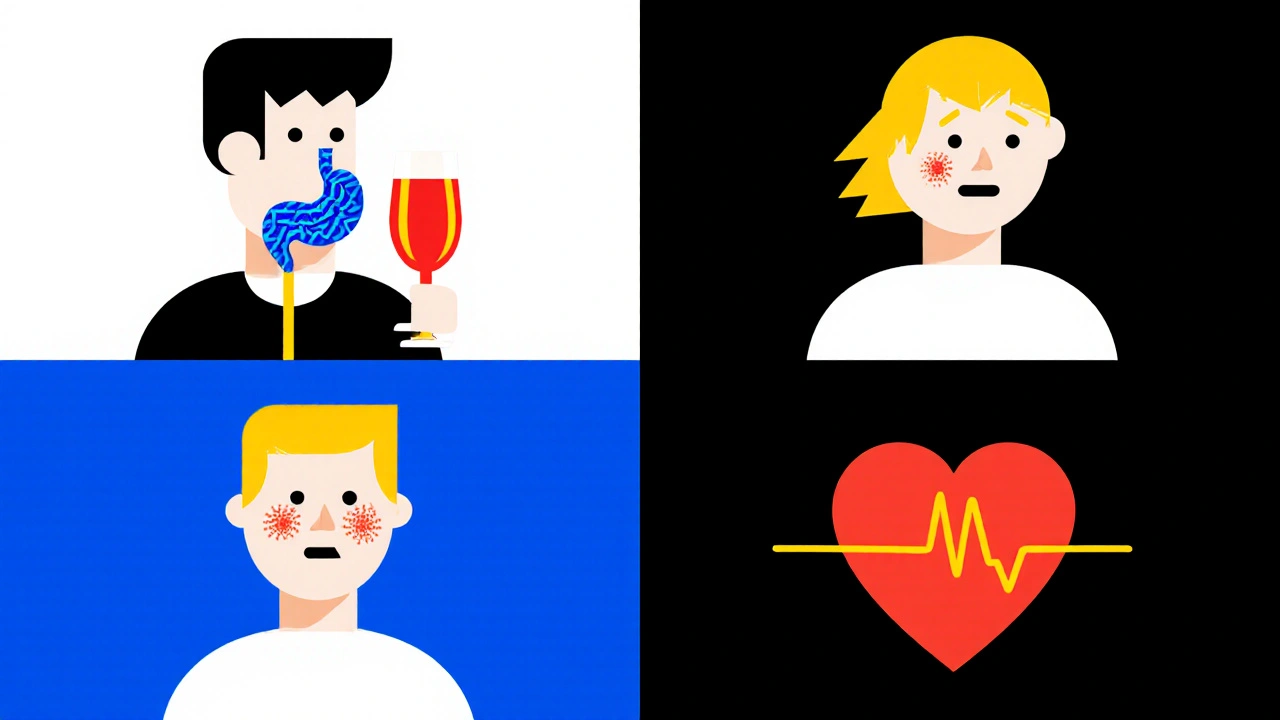

Common Symptoms You Might Notice

- Gastrointestinal upset: nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain are typical, but they intensify when alcohol irritates the stomach lining.

- Headaches and dizziness: both alcohol and clarithromycin can cause central nervous system effects; together they may feel like a mini‑migraine.

- Flushing or skin rash: a histamine‑mediated reaction that can mimic an allergic response.

- Heart palpitations: rare, but high clarithromycin levels can affect cardiac rhythm, especially in patients with pre‑existing conditions.

If any of these symptoms become severe-persistent vomiting, a fast heartbeat, or a rash that spreads-stop drinking immediately and contact a healthcare professional.

Comparing Clarithromycin with Other Macrolides

| Antibiotic | Alcohol Interaction Severity* | Key Metabolic Pathway | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clarithromycin | High - strong CYP3A4 inhibition | CYP3A4 | Respiratory infections, H. pylori |

| Azithromycin | Moderate - less CYP3A4 effect | CYP3A4 (minor) | STIs, community‑acquired pneumonia |

| Erythromycin | High - strong CYP3A4 inhibition | CYP3A4 | Skin infections, pertussis |

*Severity rating based on clinical reports and pharmacokinetic studies up to 2024.

Notice that azithromycin carries a lower risk because it interacts less aggressively with CYP3A4. If you anticipate occasional social drinking, some clinicians might switch you to azithromycin, but only after weighing the infection type and resistance patterns.

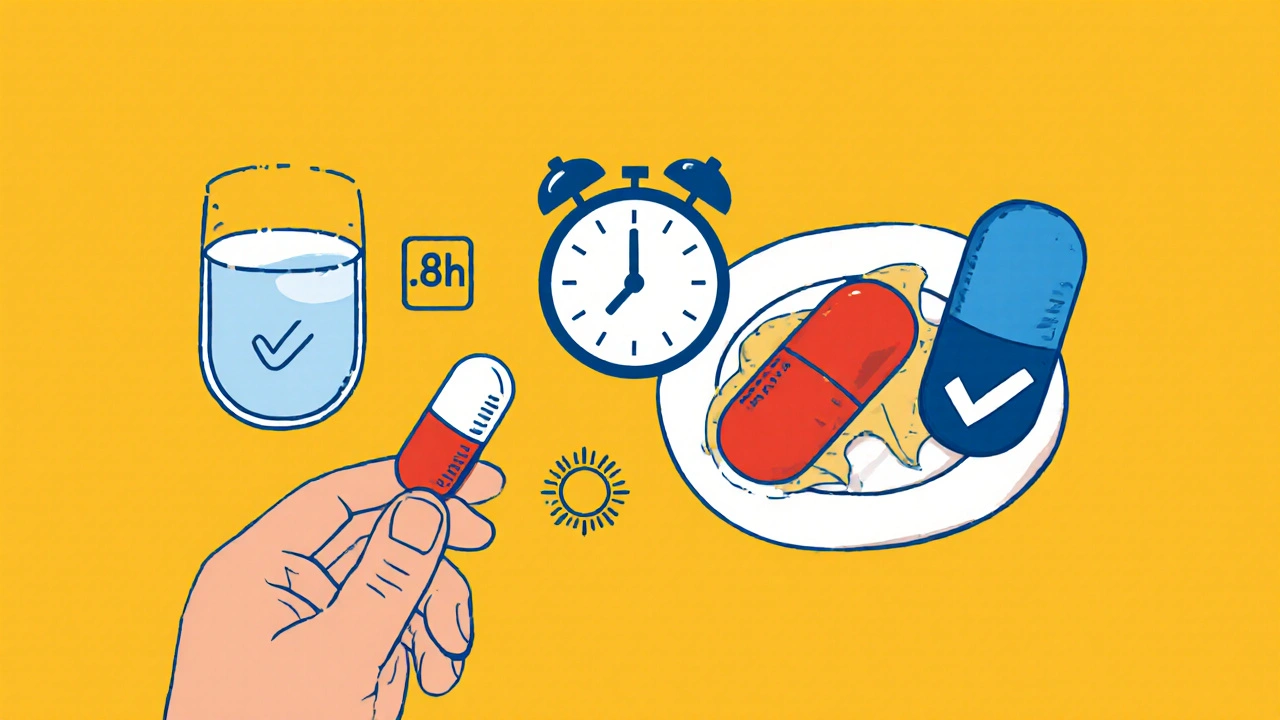

Practical Precautions If You’re on Clarithromycin

- Ask before you sip. Tell your doctor or pharmacist about any planned alcohol consumption. They can advise a suitable waiting window.

- Stick to the prescribed dose. Skipping doses and then drinking can cause fluctuating drug levels, raising toxicity risk.

- Watch your stomach. Pair the antibiotic with food (unless your doctor says otherwise) to buffer alcohol’s irritant effect.

- Hydrate. Water helps the liver flush both ethanol and drug metabolites more efficiently.

- Know the timeline. After finishing the course, wait at least 48 hours before drinking heavily, allowing residual clarithromycin to clear.

These steps are simple but can dramatically cut down on unpleasant side effects.

When to Seek Immediate Medical Help

Even though most people experience mild discomfort, a few red‑flag symptoms demand urgent attention:

- Severe vomiting or inability to keep fluids down for more than 12 hours.

- Chest pain, rapid heartbeat, or fainting spells.

- Swelling of the face or throat, indicating a possible allergic reaction.

- Yellowing of the skin or eyes - a sign of liver stress.

If any of these appear, call emergency services or head straight to the nearest hospital. Mention that you’re taking clarithromycin and have consumed alcohol.

Key Takeaways

- Clarithromycin blocks the CYP3A4 enzyme, making alcohol‑induced liver strain more likely.

- Common side effects-nausea, headache, flushing-can worsen when you drink.

- Azithromycin offers a lower‑risk alternative for patients who expect occasional drinks.

- Follow clear precautions: stay hydrated, eat with the medication, and allow a buffer period after the course.

- Seek urgent care for severe gastrointestinal, cardiac, or allergic symptoms.

Can I have a glass of wine while taking clarithromycin?

A single small glass (about 100 ml) is unlikely to cause serious problems for most healthy adults, but even modest alcohol can boost clarithromycin’s side effects. The safest route is to avoid alcohol until you finish the antibiotic or discuss a low‑risk plan with your doctor.

Does alcohol reduce the effectiveness of clarithromycin?

Alcohol doesn’t directly neutralise the antibacterial action, but it can interfere with absorption and increase side effects, which may lead you to skip doses-ultimately lowering treatment success.

Are there long‑term liver risks from mixing the two?

Short‑term occasional drinking rarely causes lasting liver damage, but repeated heavy drinking while on clarithromycin can stress the liver enough to trigger transient enzyme elevation. Chronic abuse should be avoided entirely.

What alternatives exist if I can’t avoid alcohol?

Your clinician might switch you to azithromycin, which has a milder effect on CYP3A4, or prescribe a non‑macrolide such as doxycycline, depending on the infection. Always let your prescriber know your drinking habits.

How long after stopping clarithromycin is it safe to drink?

Most guidelines recommend waiting at least 48 hours after the final dose, giving the drug enough time to clear from the bloodstream. For heavy drinkers, a longer wash‑out (72 hours) is prudent.

Write a comment